There are at least 20 uncontacted tribes living in the Peruvian Amazon, all face catastrophe unless their land is protected

Survival has been calling on the Peruvian government to protect land inhabited by uncontacted tribes since the 1970s.

Today, five reserves have been created for uncontacted tribes, and Peru has ratified laws that uphold the tribes’ right to be left alone.

But now the threats are greater than ever. Six reserves are still unprotected, illegal loggers and miners are invading the forest, and oil and gas concessions cut across more than 70% of Peru’s Amazon region.

We’re campaigning to ensure the government upholds uncontacted tribes’ right to their land and prevents outsiders from invading it.

The greatest threats to Peru’s uncontacted tribes are oil workers and illegal loggers.

More than 70% of the Peruvian Amazon has been leased by the government to oil companies. Much of this includes regions inhabited by uncontacted tribes.

Oil exploration is particularly dangerous to the tribes because it opens up previously remote areas to other outsiders, such as loggers and colonists. They use the roads and paths made by the exploration teams to enter.

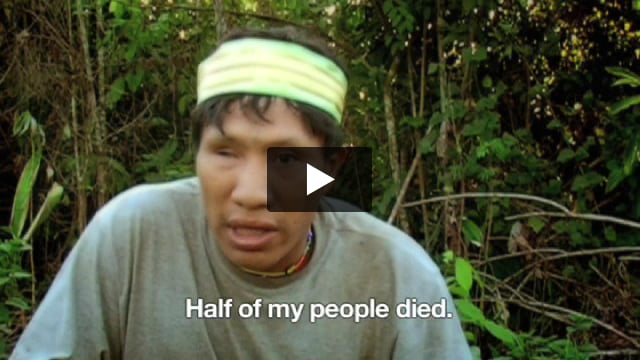

My people all died. Their eyes started to hurt, they started to cough, they got sick and died right there in the forest. Nahua woman describes contact

Shell and the Nahua tragedy

In the past, oil exploration has led to violent and disastrous contact with uncontacted tribes.

In the early 1980s, exploration by Shell led to contact with the uncontacted Nahua tribe. Within a few years around 50% of the Nahua had died.

Now a consortium of companies led by Argentine Pluspetrol is working on the Nahua’s land and plans to expand the massive gas project. It is Peru’s largest gas field, and is known as ‘Camisea’.

Camisea lies inside a reserve for uncontacted and uncontacted tribes that includes the Nanti and Matsigenka people. Further expansion of the project could result in the demise of these vulnerable tribes.

Meanwhile, Peru describes its policy to international companies as ‘open door’. The government is actively encouraging new companies to explore in areas inhabited by uncontacted tribes including the Mashco-Piro and Isconahua.

Mahogany: ‘Red gold’

The other principal threat is illegal loggers, many of them after mahogany. Known as ‘red gold’, mahogany commands a very high price on the global market.

Peru’s rainforest has some of the last commercially viable mahogany stands anywhere in the world, prompting a ‘red gold fever’ for the last of them.

Tragically, these are the same regions where the uncontacted tribes live, meaning that loggers invade their territory and contact is almost inevitable.

In 1996 illegal loggers forced contact with the Murunahua people. In the following years over 50% of them died, mainly from colds, flu and other respiratory infections.

Loggers have also been forcing members of an uncontacted tribe to flee from Peru across the border into Brazil.

The evidence

A vast amount of evidence, including video footage, audio material, photographs, artifacts, testimonies and interviews, has been collected over the years.

For example, on the 18th of September 2007 a plane chartered by the Frankfurt Zoological Society checking for the presence of illegal loggers flew over a remote part of Peru’s south-eastern rainforest. By chance they came across a group of twenty-one uncontacted people, probably members of the Mashco-Piro tribe, in a temporary fishing camp on a river bank.

Just six weeks after the sighting, Peru’s President Garcia wrote in a newspaper article that the uncontacted tribes had been ‘created by environmentalists’ opposed to oil exploration.

Lifestyle

Almost all the uncontacted tribes are nomads, moving across the rainforest according to the seasons in small, extended family groups.

In the rainy season, when water levels are high, the tribes, who generally do not use canoes, live away from the rivers deep in the rainforest.

During the dry season, however, when water levels are low and beaches form in the river bends they camp on the beaches and fish.

Turtle eggs

The dry season is also the time of year river turtles appear on the beaches to lay their eggs, burying them in the sand.

The eggs are an important source of protein for uncontacted people, and they are experts at finding and digging them up.

The tribes’ appearance on the beaches means that they are most likely to be seen by loggers, other outsiders or neighbouring, contacted tribes at this time of year.

Besides turtle eggs, uncontacted people eat a variety of meat, fish, plantains, nuts, berries, roots and grubs. Animals hunted include tapir, peccary, monkey and deer.

Uncontacted Tribes

Survival estimates there are at least 20 uncontacted tribes in Peru. They live in the most remote, uncontacted regions of the Amazon rainforest, but their land is being rapidly destroyed by outsiders.

They include the Kakataibo, Isconahua, Matsigenka, Mashco-Piro, Mastanahua, Murunahua (or Chitonahua), Nanti and Yora.

Multiple threats

All of these peoples face terrible threats – to their land, livelihoods and, ultimately, their lives. If nothing is done, they are likely to disappear entirely.

Uncontacted tribes are extremely vulnerable to any form of contact with outsiders because they do not have immunity to Western diseases.

International law recognizes the tribes’ land as theirs, just as it recognizes their right to live on it as they want to.

Following first contact, it is common for more than 50% of a tribe to die. Sometimes all of them perish.

That law is not being respected by the Peruvian government or the companies who are invading tribal land.

Uncontacted for good reason

Everything we know about these uncontacted tribes makes it clear they seek to maintain their isolation.

On the very rare occasions when they are seen or encountered, they make it clear they want to be left alone.

Sometimes they react aggressively, as a way of defending their territory, or leave signs in the forest warning outsiders away.

Uncontacted people have suffered horrific violence and diseases brought by outsiders in the past. For many this suffering continues today. They clearly have very good reason not to want contact.

What can we do about it?

Survival is urging the Peruvian government to protect these uncontacted tribes by not allowing any oil exploration, logging or other form of natural resource extraction on their land.

The government must recognize uncontacted people as the owners of their land.

After a Survival campaign in the 1990s, in collaboration with local indigenous organisation FENAMAD, the oil company Mobil pulled out of an area inhabited by uncontacted tribes in south-east Peru.

Please help us fight for the rights of the world’s most vulnerable peoples.

Act now to help the Uncontacted Tribes of Peru

Your efforts are crucial in defending the Uncontacted Tribes. Get involved in this urgent effort in the following ways.

- Writing a letter to the Peruvian government can make a real difference.

- Donate to the Uncontacted Tribes campaign (and other Survival campaigns).

- Write to your MP or MEP (UK) or Senators and members of Congress (US).

- Write to your local Peruvian embassy

- If you want to get more involved, contact Survival…

Join the mailing list

More than one hundred and fifty million men, women and children in over sixty countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Uncontacted Tribes of Peru

Ecuador: Victory for uncontacted tribes as oil drilling blocked in historic referendum

People in Ecuador have voted to block oil drilling on uncontacted tribes’ land in the Yasuní National Park.

Peru: “Genocide Bill” scrapped as Indigenous people claim victory

A key Congressional committee in Peru has effectively blocked a draft law, labeled the “Genocide Bill” by Peru’s Indigenous people.

NEWS: Peru & Brazil’s Indigenous people join forces to combat “Genocide Bill”

An Indigenous delegation from Brazil has flown to Peru to join forces with Indigenous organizations to stop the “Genocide Bill.”

Peru: new “Genocide Bill” could wipe out all the country’s uncontacted tribes

A "Genocidal Bill" is being cosidered in Peru's Congress, which could wipe out uncontacted tribes across the nation.

Anglo-French oil company threatens uncontacted tribes in Peruvian Amazon

Perenco is opposing the creation of the Napo-Tigre reserve for uncontacted tribes in Peru to keep drilling for oil.

Previously-unknown uncontacted Amazon tribe on the brink of extermination

An uncontacted tribe's existence has been confirmed - but they're already at imminent risk of being wiped out.