Refugees in our own country

In September 2013, the female chief of a Guarani community led her community in a reoccupation of their ancestral land. Survival recounts her tragic and inspiring story, with photographs by Paul Patrick Borhaug.

Damiana Cavanha stands by the side of a Brazilian road, a blue-feathered maraca made from a pumpkin gourd in one hand, and starts to sing. The ground is littered with rubbish; behind her stand huts constructed from corrugated iron, plastic sheeting and tarpaulin.

Lorries thunder past; the noise drowns out her invocations.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

Damiana is from the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe, who are thought to have been one of the first peoples to be contacted after Europeans arrived in South America.

© Paul Enkelaar

Once occupying a homeland of forest and plains in Brazil totaling some 350,000 square kilometers, the Guarani hunted freely for game on their homelands, and planted manioc and corn in their gardens.

Land is everything to the Guarani: it provides their livelihood and shapes their languages and beliefs. It is their ancestors’ burial place and the inheritance of their children. During the past 100 years however, almost all their forest land has been stolen from them and turned into vast, dry networks of cattle ranches, soya fields and plantations of towering sugar cane.

© Survival

A decade ago, cattle ranchers intimidated Damiana and her family, evicting her from her ancestral lands.

The Apy Ka’y community has since lived in squalid conditions by the highway. On 15 September 2013, however, they carried out a courageous ‘retomada’ (re-occupation) of the sugar cane plantation that has taken over their ancestral land.

We decided to reoccupy part of our traditional land where there is a well of good water and a bit of remaining forest, said Damiana this week. Faced with the threat of death, the loss of our relatives and so much suffering and pain, we decided for the fourth time to reoccupy our land.

© Survival

For as long as they can remember, the Guarani have been searching for a place revealed to them by their ancestors, where people live free from pain and suffering; a place they call the land without evil .

But they did not find it here, on a red patch of no-man’s land, where flies swarmed in hot shelters and polluted water was collected in plastic bottles thrown from passing cars.

© Rodrigo Baleia/Survival

The Apy Ka’y community’s only water source was one that is polluted by chemicals used to spray soya and sugarcane plantations.

When it rained, we drank dirty water like dogs, says Damiana.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

In the past few years, Damiana’s husband and three of her sons have been run over and killed on the highway.

They are buried on their ancestral land, which is now a fenced sugar cane plantation.

Damiana has taken great risks in breaching the area in order to pray at their gravesides.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

They were my three warriors, says Damiana, of her sons who were killed on the road.

The location of their graves was a factor in Damiana’s decision to carry out the retomada.

We decided to return to the land where three of our children are buried, she said.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

In August 2013, a fire had raged through the Apy Ka’y camp, forcing Damiana and her community to flee as her shelter smouldered and possessions were lost to the blaze.

The fire was reported to have started on the São Fernando sugarcane plantation and mill that occupy her ancestral land. It was not the first time her camp had been engulfed by flames; in September 2009, gunmen set the Apy Ka’y shelters alight and attacked members of Damiana’s community.

The Guarani now say that the characteristic reddish colour of the earth is tinted by the spilled blood of their people.

© Spensy Pimentel/Survival

The loss and destruction of their lands have been at the root of the Guarani’s appalling suffering.

Many have succumbed to mental anguish. Figures reveal that, on average, at least one Guarani has committed suicide every week since the start of this century. According to Brazil’s Health Ministry, 56 Guarani Indians committed suicide in 2012 (the actual figures are likely to be higher due to under-reporting.) The majority of the victims are between 15 and 29 years old, but the youngest recorded victim was just 9 years old.

The Guarani are committing suicide because we have no land, said a Guarani man. In the old days, we were free. Now we are no longer. So our young people think there is nothing left.

They sit down and think, they lose themselves and then they commit suicide.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

Our shelters, clothes, food, pots, pans and mattresses have all been burned, says Damiana.

We have lost everything, except the hope we will return to our ancestral land.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

A ‘retomada’ has long been Damiana’s hope and solace: the goal that has sustained her through the brutal years of eviction, fear, humiliation, malnutrition, bereavement, illness and depression.

It is a dangerous act; other Guarani have been murdered carrying out a ‘retomada’, and the sinister presence of pistoleiros (gunmen) parked near her shelter in blacked-out jeeps has always been a constant reminder of the value of land in Brazil, and the price people pay for their actions. They have already received three death threats, and say that an attempt was made to poison their water.

© Simon Rawles/Survival

Survival International is campaigning for the Brazilian authorities to map out Guarani territory as a matter of urgency.

In 2012, Survival successfully persuaded oil giant Shell to scrap plans to source sugar cane from lands stolen from the Guarani, and successfully lobbied judges to suspend an eviction order which threatened to force Guarani Indians of Laranjeira Ñanderu community to leave their land.

It isn’t surprising that the Guarani are taking matters into their own hands, said Stephen Corry, Director of Survival, this week. They desperately need support, or they are likely to be evicted and attacked yet again.

© Survival

Just as it is only a thin line of barbed wire that has separated the Apyka’y camp from the sugar cane plantation that has taken over their lands, so there is only a slender demarcation between the outer world of nature and the inner world of self, for the Guarani.

Their homeland is the mainstay of their identity: to live disconnected from it is to live in purgatory.

We have decided to fight and die for our land, says Damiana of this week’s retomada.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

We are refugees in our own country.

Damiana Cavanha.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

Other galleries

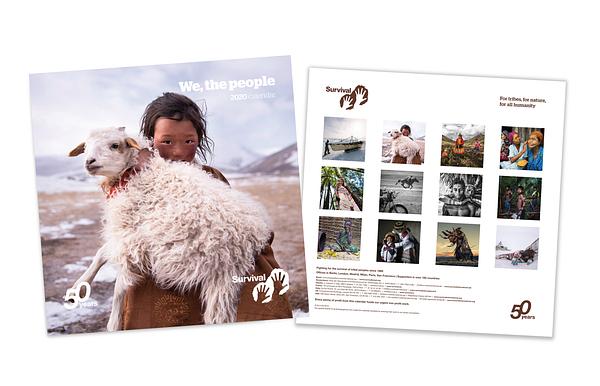

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

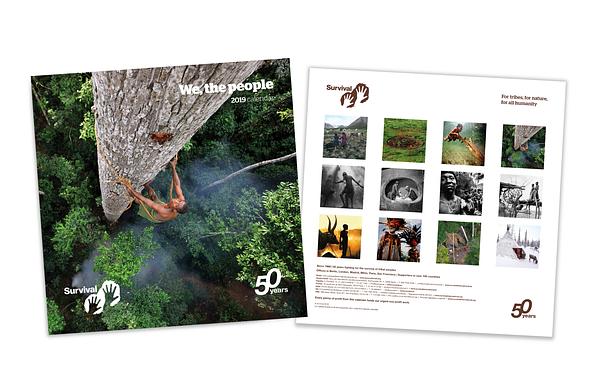

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...