Brazil's Tribes

There are around 240 indigenous tribes in Brazil today, from the savannahs and Atlantic forest of the south, to the dry interior of the north-east. Who are the tribes, how do they live and what does the future hold for them?

The Matsés are known as ‘jaguar people’ for their feline facial decorations.

To the Matsés, plants and animals have spirits just as humans do, which can ail or heal a human body.

Despite hundreds of years of contact with expanding frontier society, Brazilian Indians have, in most cases, maintained their languages and customs in the face of the massive theft of, and continuing encroachment onto, their lands.

© Christopher Pillitz

It is thought that over 10 million Indians lived in Brazil when Christopher Columbus arrived in the ‘New World’ in 1492.

Brazilian Indians have since been bombed, poisoned, tortured and gunned down by colonizers, armies and racist governments determined to profit from their lands.

In the 20th century, an average of one tribe was wiped out every year. Almost 1,500 tribes are believed to have become extinct since 1500.

© José Idoyaga/Survival

Damiana Cavanha, leader of the Guarani Apy Ka’y community, who recently spear-headed the re-occupation of her people’s land.

Brazil’s most numerous tribe, the Guarani were thought to be one of the first peoples to be contacted after the Europeans arrived in South America.

Over the past 100 years, almost all the Guarani’s land has been stolen from them and turned into vast, dry networks of cattle ranches, soya fields and sugar cane plantations. Most Guarani are now squeezed onto tiny reservations or living in squalid camps on busy road-sides.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

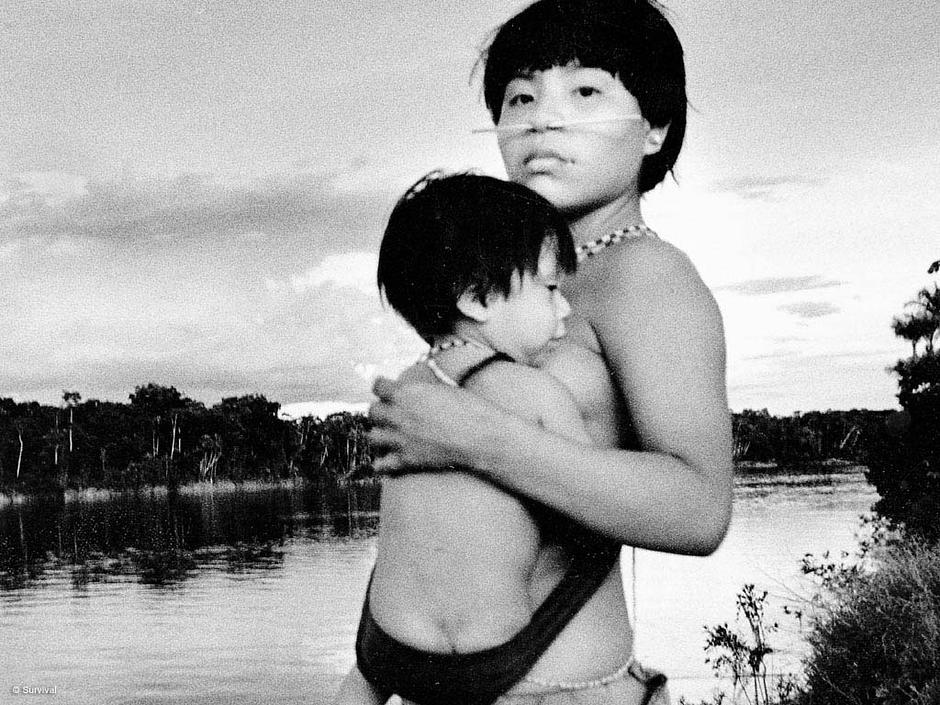

An Awá boy. The Awá are one of the last nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes in the Brazilian Amazon.

The rainforest in the eastern Amazon has long provided the Awá with everything they need to survive. They hunt for wild pigs, tapirs and monkeys with 6-foot bows, and gather nutritious forest produce, such as babaçu fruits, açai berries and honey.

The Awá keep orphaned, wild animals as pets; the women care for baby monkeys by suckling them.

© Domenico Pugliese

Awá woman, Amerintxa, with her pet capuchin.

© Domenico Pugliese

The Awá are the Earth’s most threatened tribe. They have known decades of massacre, displacement and disease at the hands of greedy landowners and corrupt politicians.

In one ambush, gunmen attacked the family of Karapiru, killing most of them. Karapiru escaped into the rainforest, where he remained on the run for 10 years, until he was discovered 600 miles from his home.

In April 2014, after a global campaign spear-headed by Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, the government-led Operation Awá successfully removed all invaders from the Awá’s land.

Survival is now calling on the Brazilian authorities to put in place a permanent land protection program to keep invaders out of the Awá’s territory.

© Sarah Shenker/Survival

Enawene Nawe men perform their most important ritual: the Yãkwa.

The Enawene Nawe tribe do not eat red meat. They are expert fishermen, possessing an array of techniques to catch the fish upon which they rely, using intricate wooden dams, spears and natural poison.

When the õha plant flowers, the four-month long Yãkwa ritual begins and the Enawene Nawe men set off for fishing camps. Two months later they return to the village, where food is ritually exchanged with the spirits.

The state government of Mato Grosso in Brazil is now building a series of dams on the Juruena river. The dams threaten the tribe, the fish they eat and their sacred ritual; in recent years, the dams have resulted in reduced fish stock, leading to the government flying in frozen fish for the Enawene Nawe.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

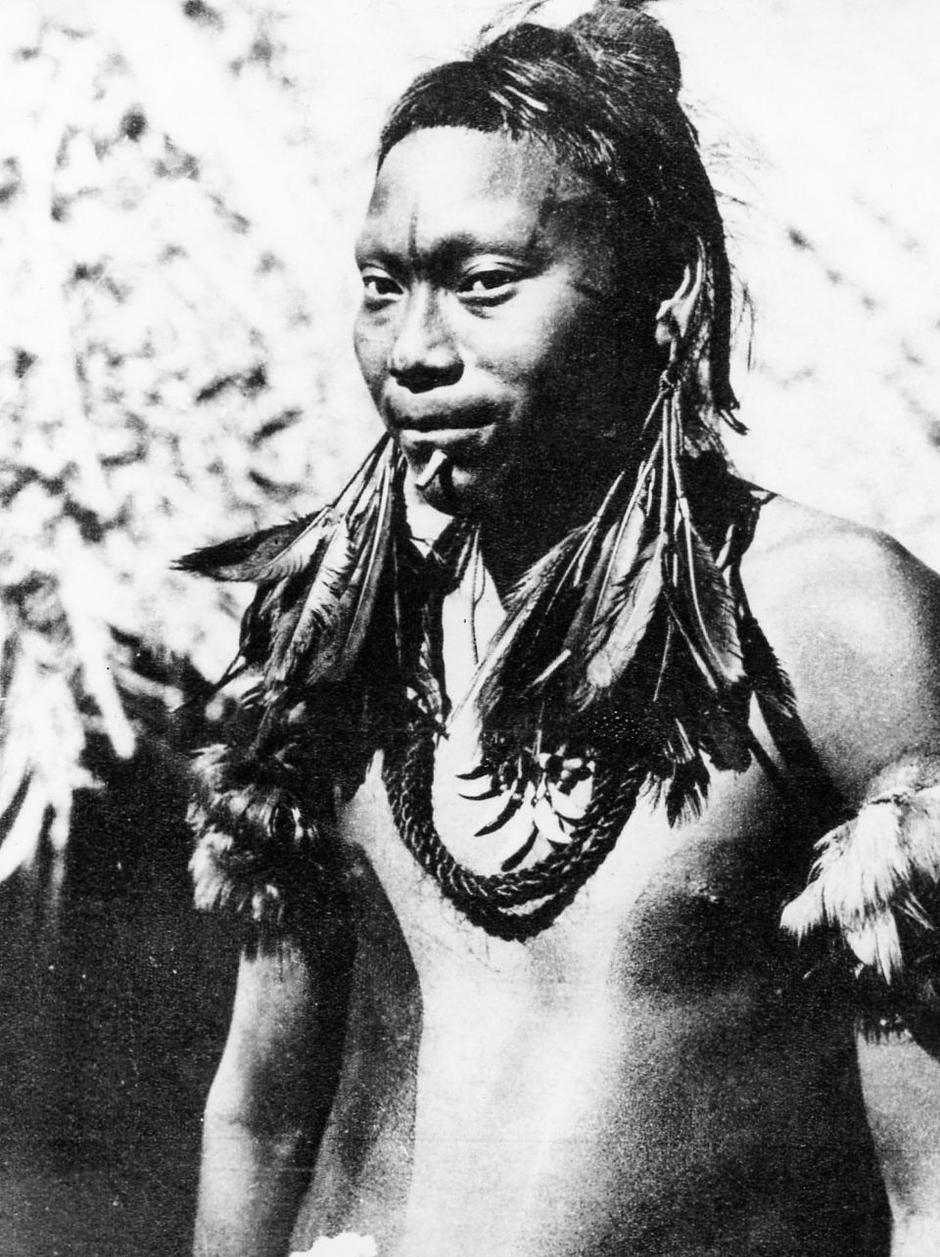

The Zo’é are a small, isolated tribe who live deep within the Amazon rainforest.

From a young age the Zo’é wear a long, wooden plug inserted into the lower lip.

Zo’é women paint their bodies with urucum – a vibrant red paste made from crushed annatto seeds.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

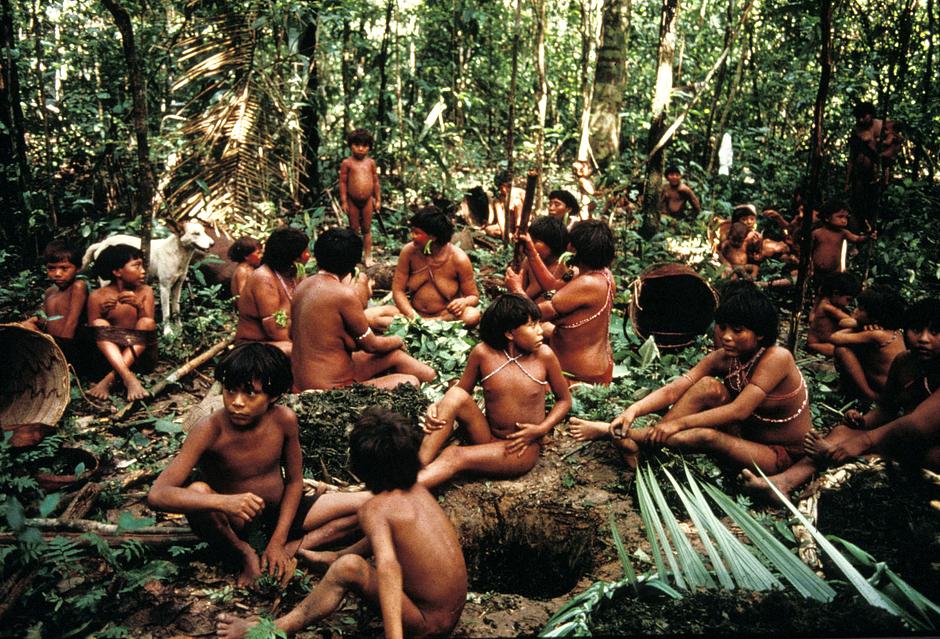

The Yanomami people are one of the largest, relatively isolated tribes in South America.

Their ancestors probably migrated across the Bering Strait between Asia and America, possibly between 15,000 and 16,000 years ago, making their way slowly down the continent to South America.

During the 1980s, approximately 40,000 illegal Brazilian gold miners invaded Yanomami land, exposing them to diseases to which they had little immunity. Within seven years, 20% of the Yanomami people died from diseases.

In 1992, their land was demarcated, following an international campaign by Yanomami spokesman Davi Kopenawa, the Pro-Yanomami Commission and Survival.

It is now the largest forested indigenous territory in the world.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

There are at least 100 uncontacted tribal peoples living in the 21st century.

Brazil’s Amazon is home to more uncontacted tribes than anywhere else in the world. According to FUNAI, Brazil’s Indian affairs department, there are at least 77 isolated groups in the rainforest.

They are the most vulnerable of all human societies on Earth. Following contact, violence and disease can quickly kill entire populations; all uncontacted tribes face catastrophe unless their land is protected.

Survival International is playing the leading role in securing their lands for them.

© G. Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

The Akuntsu are a tiny Amazonian tribe of just five individuals – smaller than a football team.

They are the last known survivors of their people and live in Rondônia state, western Brazil; they have witnessed the genocide of their people by gunmen hired by cattle ranchers.

In a few decades the Akuntsu will become extinct, and our planet will have lost a unique people, language and culture.

FUNAI is trying to expel the ranchers that surround them and linguists are now working with the Akuntsu to record and understand their language.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

Today, Brazil’s soccer stadiums are built on Indian land, and its new-found wealth comes from the dispossession of the Indians and the theft of their lands.

A constitutional amendment was recently proposed that would give Congress power in the process of demarcating tribal lands; this would weaken Brazil’s indigenous peoples’ hold on their territories. Another controversial bill would open up indigenous territories for mining, dams, army bases and other industrial projects.

Five hundred years after colonization, Brazilian Indians are still being killed for their lands and resources.

Stephen Corry, Director of Survival, said, Brazil is frequently celebrated as an economic success story – never more so than in the run-up to the World Cup. But it’s only fair to acknowledge that its economic growth is incurring an immense human cost.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

This here is my life, my soul. If you take the land away from me, you take my life.

Marcos Veron, Guarani, Brazil.

© Clive Dennis/Survival

Brazil, the largest country in South America, is home to carnival, capoeira, samba – and soccer.

An emerging economic giant, the country presents itself as a multi-cultural democracy. It is now hosting the FIFA World Cup, which is, in the words of President Dilma Rousseff, for everyone, .

Beneath the surface, however, lies a darker side: the shocking treatment of its indigenous peoples.

Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, has been campaigning for the rights of Brazilian Indians since 1969.

© Steve Cox/Survival

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

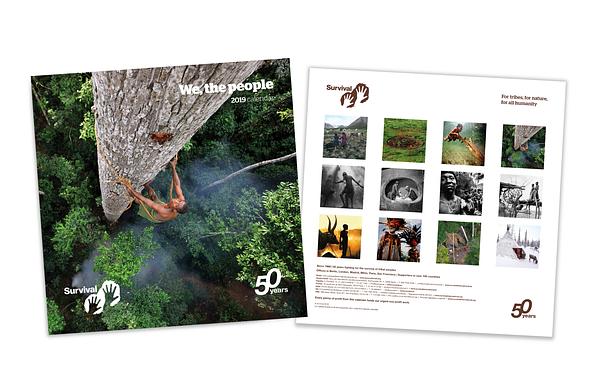

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...