Community Mapping

Lambombo, a Baka man from Cameroon, said ‘When we see the forest we think ‘that is our forest’. But now we are told by the government and the conservationists that it is not our forest.’

Many Indigenous people had well defined territories long before the countries in which they now find themselves were even imagined. These boundaries were usually ignored when country maps and conservation areas were drawn up.

Liquid error: internal

Because tribal territories have not been officially surveyed or recognised in many countries, governments and the private sector alike have been able to either ignore territorial boundaries completely or dramatically reduce them without ever consulting the tribe involved.

Tribal people can address this problem by creating their own maps of the land they have always known and the resources they have always drawn upon.

© Yoshi Shimizu/Survival

© Yoshi Shimizu/Survival

These maps illustrate a tribe’s wealth of knowledge about their land, and make it easier for others to understand it. They are a good tool for tribes when asserting their rights, and can make it harder for governments to deny them.

When the Botswana government tried to evict the Bushmen from the Central Kalahari the community created detailed maps of their territories showing how they use their land. These maps were used in the Bushmen’s successful court battle to win back the right to live on their land.

One of the Bushmen who took part in the mapping process told Survival ‘We the Bushmen know our land. We name everything; the bushes, the plants and the trees; they are all named after things that have happened.

‘The Bushmen know our land better than anyone and we mapped it the way we know it. Now it’s on paper, it’s been documented.’

Community mapping is not perfect, and the maps do not on their own guarantee a tribe’s control over their land. But they can be a powerful tool for tribal peoples who need to defend their land and resources from those who would snatch them away.

Mapping and Conservation

The best conservation projects start with people. The big conservation organisations are increasingly recognizing that without the support of local people, protected areas are likely to fail, especially where the locals are denied access to vital resources without suitable alternatives.

Liquid error: internal

Successful protected areas must gain the support and trust of the tribal people living in the region, by talking with them from the outset and working on the basis of obtaining their free, prior, and informed consent to the project.

Before conservation areas are marked out and management plans put in place, community maps must be drawn up to establish how the land is used, when, and by whom.

Armed with this information, tribal peoples and conservationists can work together to establish ways to secure the tribe’s livelihood while also protecting region’s ecology.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

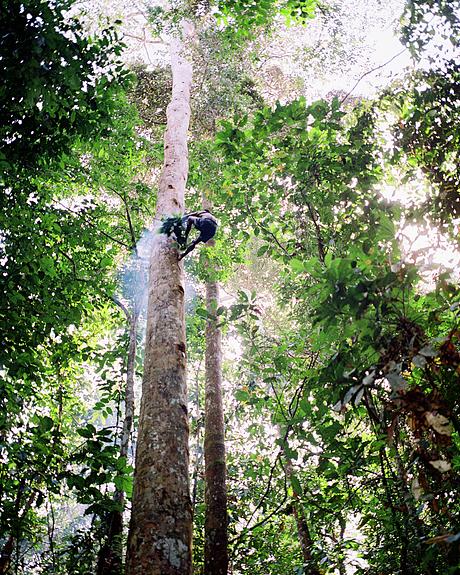

Baka and Bagyeli “Pygmies” in Cameroon have been mapping their traditional territories using Global Positioning System (GPS) devices. With the results, they can clearly show that national parks such as Boumba Bek or Campo Ma’an, as well as logging and safari hunting concessions, are part of their ancestral homes.

There is a long way to go before the Baka’s and Bagyeli’s forest rights are properly enforced, but the maps have been a constructive start.

The problem with maps

Drawing up community maps can be fraught with difficulty, especially for nomadic peoples, but are a vital tool for demonstrating that nomads and hunter gatherers do not ‘roam’ random areas, but have clearly defined territories and complex systems of collective use of the land’s resources.

Liquid error: internal

By marking a ‘village’ location on a map, nomadic communities run the risk of being forced to stay in that location, even during times of hardship when they would normally relocate to a different area.

Maps can also signal to outsiders the location of specific, valuable resources leading to a risk of exploitation, and can make it easier for individuals to sell off community land.

© John Palmer/Survival

© John Palmer/Survival

Maps are not necessarily a quick way of recognising rights. The Wichi, with help from Survival and others, successfully mapped sections of their territories, resulting in a decree to recognise their land rights. But, 19 years later, those rights are still being violated.

Once a map is made, the next step is getting people to recognise and respect it and getting the authorities to acknowledge and protect the tribe’s collective ownership rights to their land.

Sign up to the mailing list

Our amazing network of supporters and activists have played a pivotal role in everything we’ve achieved over the past 50 years. Sign up now for updates and actions.