Why Indigenous expertise is crucial to tackling the climate crisis

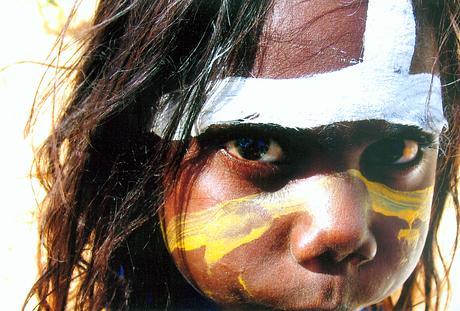

© Sinem Saban/ Survival

© Sinem Saban/ SurvivalMore than 1,500 homes have been destroyed in the apocalyptic inferno that’s ravaging Australia. Their owners left everything behind and have nothing to come back to. No amount of insurance pay-out can possibly compensate for the loss of objects whose value can’t be measured in money: kids’ drawings, gifts from old friends, and family photos are all now gone forever.

66-year-old Phil Sheppard evacuated his property in Hunter Valley, NSW, when the flames began to close in. He watched online as the fire seemed to swallow up the main house and the huts adjoining it, and he anticipated devastation on his return.

But Phil was wrong: “I came around the bend and could see my hut still standing, I just couldn’t believe it,” Mr Sheppard told the Sydney Morning Herald. “It burnt right around the house … it was as if somebody had been here watching it and putting it out, but there wasn’t, there was nobody here at all.”

Phil ascribes this seemingly miraculous survival to what the Australians call cultural burning: an Indigenous land management technique that is not only practiced by the First Nations of Australia, the US and Canada, but also by many other Indigenous and tribal peoples across the world.

A scene from the catastrophic Amazon fires in 2019. When fire services collaborated with local tribes in the Brazilian savannah, the number of dry season fires decreased by 57 percent.

Not only did banning cultural burning lead to an increase in the incidence and severity of wildfires, but scientists have come to understand that fire plays an integral role in many ecosystems. For example, there are species of plants that actually depend on fire to reproduce. Evidence now proves that, around the world, not only do Indigenous and tribal people play crucial roles in nurturing and maintaining balance in their environments, they actively enhance biodiversity. Banishing them from their land or banning their ways of life can have serious ecological consequences.

Curtis Taylor, a filmmaker and young leader of the Martu people, an Aboriginal nation of Australia’s Western Desert, told the New York Times:

“A lot of Martu people say that if there’s no people out in the country, then all the animals become absent. When the people and animals are absent, then the country becomes sick or unwell. There’s no balance there.”

But the lessons of history are not being learned, and dominant societies continue to violently force Indigenous and tribal peoples from their lands and ignore their expertise because of the racist misconception that people who live off the land are somehow “primitive.” People who live by hunting and gathering are seen as the “bottom” of this made-up hierarchy, but you need to be an expert biologist, an adept geographer, and a skilled engineer to make your living this way.

A Baka woman gathers forest produce.

The Baka people of Congo basin hunt and gather for subsistence. They have 15 different words for elephant, depending on the animal’s age, sex and temperament and they can identify easily when and where poachers are in their forest. So why is no one listening to them? Worse still, their land is being stolen and their lives and livelihoods destroyed by the conservation industry itself; indeed, the biggest conservation organization on the planet is complicit. Residents of a Baka village in Messok Dja told Survival International:

“WWF arrived in our forest and is establishing boundaries without our consent. No one has even explained to us. They just told us that we no longer had the right to go in the forest. Already the ecoguards are making us suffer. They beat people but they don’t protect elephants.”

Beating people up and stealing their land is illegal and inhumane, which is more than grounds enough for us to stand against the behavior of WWF and other perpetrators. But separating tribal people from their land and banning their ways of life and land management techniques also means that their knowledge and expertise will be eroded.

Click here to support the Baka people

Indigenous knowledge is not just another resource that westerners can exploit for their own benefit. It does not belong to us and never can: mostly it is not written down and lives, breathes and grows inside people. Of course every single person on the planet must have their human rights upheld unconditionally, but the climate emergency means that disregarding Indigenous peoples’ rights is not only wrong in itself, it is potentially fatal to us too. It would be idealistic to say that Indigenous wisdom alone will save us from the climate crisis, but it is the most intimate understanding humanity has of some of Earth’s most important ecosystems. This is one of the most potent weapons in the fight to save our planet.

© John Miles/ Survival

© John Miles/ SurvivalAboriginal cave paintings, Western Arnhem Land, Australia. The Indigenous peoples of Australia are the longest-running civilizations on Earth: their ancestors first arrived on the continent over 60,000 years ago.

Our society suffers greatly from its imperialist assumption that those “other” societies, who live off their land and have little to do with the globalized market economy, have a less sophisticated understanding of things than we do, and we often dismiss their knowledge and worldviews as myths and superstition. However, it is our own science that is proving us wrong on this, in myriad examples worldwide.

The Alawa people of Australia’s Northern Territory use the word “Jarulan” to describe a unique type of wildfire; one that has been intentionally started by a bird. Jarulan is not a myth, it is not figurative, and nor is the bird some kind of metaphor: this is literally true. In a 2017 research paper, scientists confirmed that there are not one but three species of birds that spread fires deliberately to flush their prey out into the open.

While most scientific studies collect their data over months or years, Indigenous expertise is accumulated over millennia, and this is a perspective we cannot afford to ignore. Over 230,000 people died in the 2004 Asian tsunami, which seemed to come without warning. However, the tribal peoples of the Andaman Islands did recognise the signs and took evasive actions which kept them safe; these communities were largely unaffected by the disaster.

Western society tends to see the natural world as a resource for us to exploit, either for pleasure or for profit, and likes to think that humans are somehow separate from or even “above” nature. On the other hand, most Indigenous worldviews understand human beings and the environment they inhabit as inseparable and mutually interdependent.

In his book The Falling Sky, Yanomami shaman Davi Yanomami writes:

“The white people already have more than enough metal to make their merchandise and their machines; land to plant their food; cloth to cover themselves; cars and airplanes to move in. Yet they covet the metal of our forest to make even more of these things though their factories’ foul breath is already spreading everywhere… its darkness may descend to our houses so that the children of our children will stop seeing the sun.”

It’s time to listen.