The Ashaninka

The Ashaninka of Acre state, Brazil, have recently reported encountering dozens of uncontacted Indians close to their community in Simpatia village.

The village of Simpatia in Brazil’s Acre state.

Mist rises from the rainforest as two Ashaninka children look out across the green canopy of their hilltop home.

The Ashaninka are one of South America’s largest tribes. Their homeland covers a vast region, from the Upper Juruá river in Brazil to the watersheds of the Peruvian Andes.

Recently, the Simpatia Ashaninka have reported unusual encounters with dozens of uncontacted Indians close to their homes. It is believed that these uncontacted tribes have fled into Brazil from Peru to escape the waves of illegal loggers invading their territory, a situation with which the Ashaninka are familiar.

For over a century,colonists, rubber tappers, loggers, oil companies and Maoist guerillas have invaded their lands. “Their story of oppression and land theft is echoed in the lives of tribal peoples across the world,” says Stephen Corry, former Director of Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Ashaninka traveling by boat to visit neighbors in Acre state, Brazil.

It is thought that the traditionally semi-nomadic Ashaninka have lived for thousands of years in the Peruvian Selva Central, where the Andean foothills flatten out into the Amazonian rainforest.

During the late nineteenth century, some fled across the border into Brazil’s Acre state when Peru conceded vast tracts of rainforest to foreign companies for rubber tapping and coffee plantations. This resulted in the displacement of thousands of Ashaninka from their homes.

“The vulcanization of latex and the ‘rubber boom’ that swept through this part of the Amazon wiped out 90% of the Indian population in a horrific wave of enslavement, disease and appalling brutality,” says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights.

Today, the Ashaninka of Brazil number around 1,000, living mostly along the Amônia, Breu and Envira rivers, while the majority still lives in Peru. The total Ashaninka population is estimated at approximately 70,000.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Ene valley, Peru.

The Ashaninka in Brazil avoided the horrors experienced by the Peruvian Ashaninka during the 1980 and 90s, when thousands were caught up in the internal conflict between the Maoist Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) and counter-insurgency forces.

The state of war brought disastrous consequences for the Ashaninka of Peru: assassination of leaders, torture, forced indoctrination of children and executions.

It is thought that thousands of Ashaninka were displaced, and many killed or taken captive from their forest communities by the Sendero Luminoso. Dozens of Ashaninka communities disappeared altogether.

“Our history is one of constant abuse: we were enslaved during the rubber boom, forcibly removed from our territory and subjected to cruel atrocities during the civil war that has unfolded in our territory since the 1980s,” said the Ashaninka in a 2009 statement.

© Angela Cumberbirch

Hunting game in the rainforest in Acre state, Brazil.

The geographically distinct Ashaninka communities are united by shared ways of life, language and beliefs.

Like many Amazonian tribes, their lives are profoundly connected to their rainforest homelands. Ashaninka men spend much of their time hunting in the forest for tapir, boar and monkey. The game supplements crops such as yam, sweet potatoes, peppers, pumpkins, bananas, and pineapples that are grown by women in swidden gardens.

The Ashaninka periodically migrate to a different area, so allowing the rainforest to regenerate.

“This way of farming is good for the rainforest because that is the way the rainforest is’, says an Ashaninka man. ‘We live in the forest and we respect it.”

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Observing game in the forest canopy, Acre state, Brazil.

Beehives in the high boughs of vast trees provide honey, while ants, forest fruits and a root called mabe are also eaten by the Ashaninka.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

A young Ashaninka boy in Acre state practices his archery skills using arrows with blunt tips.

Ashaninka children learn self-sufficient skills – such as hunting and fishing – at an early age.

In Acre state, however, the illegal logging of mahogany and cedar trees in the 1980s has decimated the Brazilian Ashaninka’s forest home. They remember this period as the ‘time of logging’, when they experienced hardship and poverty not known before contact with the loggers (brancos). Many Ashaninka died from exposure to diseases to which they had no immunity – an experience shared by other isolated tribes. Following first contact, it is common for more than 50% of a tribe to die.

The more Ashaninka lands are encroached on by loggers, the more the danger grows that their children will no longer learn skills that have been passed down the generations, and their ancestral knowledge will eventually disappear.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

A young Ashaninka mother, wearing a traditional kushma robe, plays with her baby daughter.

Ashaninka children are given a provisional name when they start walking, and an official name at the age of seven.

The Ashaninka believe that children can inherit the characteristics of any animal eaten by their mothers during pregnancy. Expectant mothers therefore refrain from eating turtle meat, for fear their child will be slow-moving.

During adolescence, Ashaninka girls learn to make the traditional robe, called a kushma, by spinning, dyeing and weaving wild cotton on loom.

“Like many tribal peoples, Ashaninka have lived – and still live – in complex societies, where the solidarity of the group is of utmost importance,” says Stephen Corry.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Ashaninka boy, Acre state, Brazil.

Ashaninka apply daily face-paint in designs that reflect their moods.

The paint is made from the rose-colored seeds of the achiote tree which, when crushed, produce a pigment commonly known as urucum. South American Indians have used urucum for centuries, yet it is only in recent years that it has arguably become one the world’s most important natural food colorants.

“Annatto is one of the many gifts that tribal people have given humanity, and is testament to their encyclopaedic knowledge of their ecosystems,” says Stephen Corry.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Brazilian Ashaninka children play football with a ball made of rubber tapped from trees in Acre state.

The Ashaninka children’s football is made from natural rubber; the goal posts are made from tree trunks bound with reeds.

During the rubber boom that started in the late nineteenth century, the Ashaninka in Peru were forced by European companies to work as slaves.

The search for rubber profoundly changed the history of the region and had dramatic consequences for its indigenous populations; it is thought that as much as 80% of the Ashaninka population died from disease, exhaustion and massacres.

“When the West began its marriage to the motor car, its love letters were written in Indian blood,” says Stephen Corry.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

A lone Ashaninka crosses the river in a dug out boat, Acre state, Brazil.

In 2011, 15 Ashaninka communities from Peru and Brazil teamed up to investigate the illegal activities of loggers on the Brazilian side of the border.

The five-day trip uncovered widespread evidence that loggers were active in the area, with trees marked for felling in Brazilian Ashaninka territory, which is protected by law.

The expedition’s findings were recorded on GPS systems and presented to Brazilian authorities. The team is calling for a more efficient monitoring system, to be complemented by the full participation of local Indians.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Ene River valley, Peru.

In 2003 the Ashaninka of the Ene River valley in Peru were granted Communal Reserve rights to a portion of their ancestral lands, in the form of Otishi National Park.

In June 2010, however, the Brazilian and Peruvian governments signed an energy agreement that allowed Brazilian companies to build a series of large dams in the Brazilian, Peruvian and Bolivian Amazon. In the same year, the dam was stopped through a legal action presented by the Central Ashaninka del Rio Ene (CARE).

The dam, however, is still listed on the government’s energy plan. The 2,000 megawatt Pakitzapango dam proposed for the heart of Peru’s Ene valley could still displace as many as 10,000 Ashaninka.

If built, the dam would drown the Ashaninka villages situated upstream, and open up other areas to logging, cattle ranching, mining and plantations.

© Angela Cumberbirch

The spread of illegal logging in Brazil has also threatened several groups of uncontacted Indians who live nearby.

In June 2014, Survival reported that Brazilian officials have warned that uncontacted Indians face imminent “tragedy” and “death”. This follows a dramatic increase in the number of sightings in the Amazon rainforest near the Peru border, and the sightings by the Ashaninka of Simpatia village.

José Carlos Meirelles, who monitored this region for the Brazilian government’s Indian Affairs Department FUNAI for over 20 years, said, “Something serious must have happened. It is not normal for such a large group of uncontacted Indians to approach in this way. This is a completely new and worrying situation and we currently do not know what has caused it.”

Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, is calling on the Brazilian and Peruvian governments to protect all land inhabited by uncontacted tribes and to honor their promise to improve cross-border coordination to safeguard their welfare.

http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/10308

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Other galleries

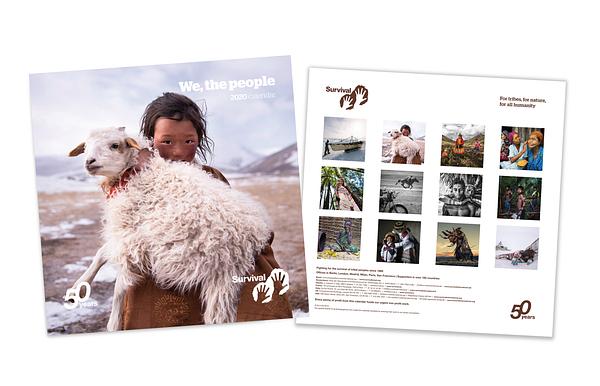

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

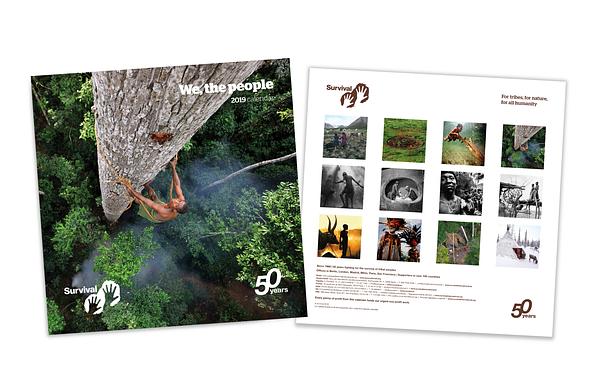

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...