Guardians of the world's rainforests

It breathes, though you don’t notice it, says Davi Kopenawa of his Amazon home. Tribal peoples have lived in balance with their rainforests for millennia: they are the original guardians.

‘We love the forest as we love our own bodies,’ say the Mbendjele ‘Pygmies’ who live in the densely forested regions of the Republic of Congo .

There are several distinct forest peoples living across Central Africa, such as the Baka, the Twa, the Aka and the Mbuti. They are commonly referred to as ‘Pygmies,’ a name many find pejorative. Each group has its own language, yet one word is common to many of them: jengi, which means the spirit of the forest.

‘Pygmy’ men will scale immense trees in search of honey, and are such proficient mimics they can imitate the sound of a distressed antelope in order to lure another out of the bush.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

In recent years the homelands of the ‘Pygmies’ have been devastated by logging, war and encroachment by farmers.

Many conservation schemes that aim to establish wilderness reserves deny the land rights of tribal peoples, who are evicted to the margins of their homelands; the Batwa ‘Pygmies’ were forcibly moved from Uganda’s Bwindi Forest in order to protect the mountain gorillas.

This variant of land theft is rapidly emerging as one of the biggest problems confronting indigenous peoples today, says Stephen Corry of Survival International

All my ancestors have lived on these lands, said a Batwa man. As a result of the eviction, everybody is now scattered.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

Penan hunters in the ancient rainforest of Sarawak in Borneo – one of the most biologically rich forests on earth.

The Penan have long lived in harmony with their forest and its vast trees, rare orchids and fast-flowing rivers.

Until the 1960s all Penan people lived as nomads, moving camp frequently in search of boar, and following the cycles of fruiting trees and wild sago palm.

Today, most of the 10-12,000 Penan have settled in riverside communities, although some are still largely nomadic.

The land is sacred, they say. It belongs to the countless numbers who are dead, those who are living and the multitudes yet to be born.

© Andy Rain/Nick Rain/Survival

The Penan call the forest okoo bu’un; the place of their origins.

Since the 1970s, the Penan’s rainforests have been cleared for logging, oil-palm plantations, gas pipelines and hydroelectric dams, says Sophie Grig of Survival International

The steep-sided valleys, that once were filled with birdsong, now resound with the noise of trucks and falling trees.

Dusty red logging roads transport bulldozers deep into the forest.

It is hard for us to look at the red land, say the Penan.

© Andy and Nick Rain/Survival

To conquistadores, colonists and corporations, the Amazon – the largest rainforest in the world – has always signified power and profit.

To 1 million Indians, it is simply home.

We Indians were born here, we live, work and we will die here, said an Harakmbut Indian from Peru.

© Hutukara/ISA

Deep in one of the remotest parts of the Brazilian Amazon, uncontacted Indians look up at an aeroplane.

There are over 100 uncontacted tribes worldwide: peoples with no peaceful contact with anyone else.

We know very little about them.

But we do know that they want to be left alone. That is their choice – and their right.

© G. Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

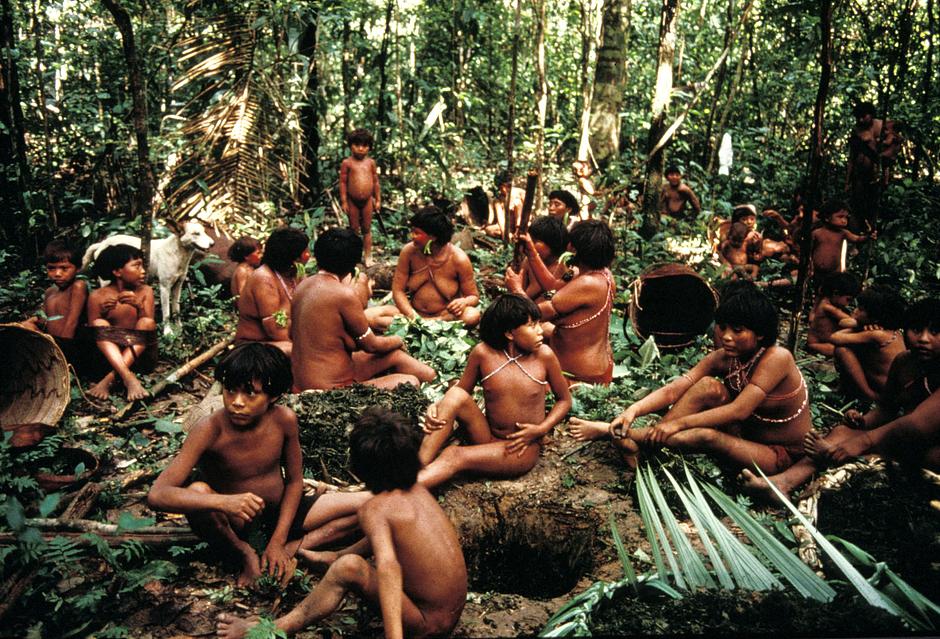

We know our forest land well, says Davi Kopenawa. As they would: the Yanomami people have lived in it for thousands of years.

Their botanical knowledge is extraordinary. Babies’ slings are made from silk-grass twine, arrow shafts from the stems of pampas grass and salt is extracted from the ashes of the great Taurari tree.

The Yanomami think and speak with the soul of the forest, says Davi.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

In recent decades, the Yanomami have suffered greatly.

In the 1980s, over 1,000 goldminers invaded their territory. As a result, nearly a fifth of the population died from measles and other illnesses to which they had no immunity.

The campaign led by Survival International resulted in the creation of the Yanomami Park in 1992. Threats are ever-present, however. Gold-miners are still working illegally in the forest, alongside cattle ranchers who are deforesting the eastern fringe of their land, says Fiona Watson of Survival.

You can’t uproot us and put us in another land_, says Davi Kopenawa._We don’t exist away from the forest. We belong in it.

© Survival

In the heart of the southern Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Enawene Nawe children throw themselves into a tannin-coloured river.

The Enawene Nawe are expert fishermen; the men spend up to four months living deep in the forest, smoking fish caught with intricate wooden dams and sending them back to villages by canoe.

All this land belongs to the yakairiti, who are the owners of the natural resources, they say.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

It was beautiful here, says an Enawene Nawe man.

Telegráfica Dam is one the many dams under construction on the River Juruena. It is killing the fish the Enawene Nawe rely on.

The tribe were not consulted about the project.

If you finish off the earth and the fish, the yakairiti will take vengeance and kill the Enawene Nawe, says an Enawene Nawe man.

© Survival International

A Guarani man stands at the side of a dusty road, his arms outstretched, a mbaraka rattle in his left hand.

The deforestation of Mato Grosso do Sul has forced many Guarani – the original owners of the forest – onto tiny patches of land.

Gone, for most, are the gardens where they planted manioc and corn; gone is the ability to hunt game freely. Instead, they are surrounded by cattle ranches, soya fields, and sugar cane plantations.

The impact of this land loss on the Guarani people has been profound. You become spiritually empty,said one man.

© Sarah Shenker/Survival

The tribal peoples of the world’s rainforests believe their homes demand greater respect.

Yet still the forests are slashed, felled and mined. As the trees fall and the smoke rises, so the indigenous communities are illegally evicted from their homes.

One of the simplest ways of preserving the world’s rainforests is to secure the rights of tribal peoples who live in them.

We, the indigenous peoples, have not forgotten that man is part of nature, says Davi Kopenawa. If we hurt nature, we also hurt ourselves. We know how to protect the forests. Give them back to us, before they die.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

The trees hold a very special meaning and purpose to all living things.

In return, they must be treated with kindness and respect.

Will their kindness to us be forgotten?

Will the respect they are due be ignored?

Will the truth they represent be, quite literally, cut down?

Mike Koostachin, Cree, Canada.

© Survival International

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...