Tribal Heroines

On International Women’s Day, Survival International profiles the lives and stories of the world’s tribal women.

For generations, industrialized societies have subjected tribal women and their communities to genocidal violence, slavery and racism in order to steal their lands, resources and labor.

On International Women’s Day, Survival International’s photographic gallery portrays not only the many tragedies that tribal women have endured, but also profiles some of the courageous and inspiring indigenous women, both past and present, who have fought – and fight on – for their lands, their ways of life and their fundamental human rights.

Pocahontas was the daughter of Wahunsonacock, the chief of the Native American Powhatan Indians. The Powhatan Indians were a confederacy of about 30 tribes; their homeland was the area known to European settlers as Virginia.

Pocahontas’ real name was Matoaka; Pocahontas was a nickname, meaning ‘little play thing’. Aged 12, she is thought to have saved an Englishman named Captain John Smith from execution, after he was captured by a group of Powhatan men.

Pocahontas was taken prisoner by the English in 1613. During captivity she changed her name to Rebecca, converted to Christianity and married Englishman John Rolfe, with whom she had a son, Thomas Rolfe. John Rolfe and Pocahontas sailed to England in 1616, where she was presented to King James I and introduced to members of English high society – as a ‘civilised savage’.

At the start of their voyage home to the U.S. in 1617, Pocahontas became seriously ill, and died in Gravesend, U.K., at the age of 22. An entry in Gravesend church parish register where she was buried reads:

Rebecca Wroth wyffe [wife] of Thomas Wroth gentleman a Virginia Lady borne was buried in the Chauncell [chancel].

Her son Thomas later returned home. Many people claim to be descended from Pocahontas.

© Courtesy of the British Museum, London.

Between Tahiti and South America lies Rapa Nui, the remotest inhabited island on earth. Also known as Easter Island, it is renowned for its Mo’ai, the large stone statues that stand sentinel on the grassy flanks of its extinct volcano.

The Moai were carved by the indigenous Rapa Nui, who had lived on the island for centuries before the first-recorded European contact in the 18th Century. In the late 19th Century their population was decimated by Peruvian slave traders, after which the island was annexed by Chile and run as a sheep ranch.

The Rapa Nui were deprived of their lands, livestock and human rights, and were forced to live in appalling conditions. The historian Stephen Fischer wrote that Rapa Nui became infamous as Pacific Islands’ worst administered colony.

In 1914, however, the Rapa Nui rebelled against the colonizers. The uprising was inspired by their female leader and visionary, Angata, who dreamed that the island once more belonged to her people.

Angata was described by Katherine Routledge, a British anthropologist living on the island at the time, as a frail old woman with grey hair and expressive eyes, a distinctly attractive and magnetic personality.

When Angata died, however, the protests died with her. It wasn’t until 1964 that Chile ended arbitrary military rule on Rapa Nui.

© Katherine Routledge

Women in industrial societies still campaign for equality with men. Many of their counterparts in hunter-gatherer societies, however, have long known equal status with men. Mutual dependence on each other’s foods – men hunt, women gather – has encouraged the development of egalitarian societies over generations.

For women of the Awá hunter-gatherer tribe in the Brazilian Amazon, an egalitarian society is normal; some Awá women even take several husbands, a practice known as polyandry.

The Hadza hunter-gatherer tribe of northern Tanzania similarly value equality highly. Hadza women have a great amount of autonomy and participate equally in decision making with men.

And when Roman Catholic missionaries arrived on the shores of the Labrador-Quebec peninsula in north-eastern Canada, many were horrified by Innu Indian women’s level of independence and power. At a time when women in Europe were generally seen as inferior to men, Innu women were far freer within and outside marriage, and often chose where and when to camp on their journeys across their sub-arctic homeland, Nitassinan.

© Domenico Pugliese – do not distribute

The Bushmen are the original people of southern Africa.

Between 1997 and 2002 almost all Bushmen were taken from their homes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and driven to eviction camps outside the reserve, where they were not only deprived of their ways of life, but humiliated by endemic racist attitudes.

Let them call us primitive. Let them call us Stone Age people. Our way of life suits us. We have seen their development, and we don’t like it, said a Bushman woman.

Xlarema Phuti, a Bushman woman healer, was forcibly evicted by the government from Molapo, to New Xade, a government eviction camp known as ‘the place of death’. Xlarema talked to Survival International about the healing powers of the Bushman’s traditional trance dance, and the sadness she has experienced since being evicted from her lands.

When I’m dancing in the trance dance I talk with the ancestors to help me heal the sick person, she said.

© Dominick Tyler

Elizabeth ‘Tshaukuesh’ Penashue is an 84 year old Innu woman from Sheshatshiu in Labrador.

For many years she has led a spring-time walk through the local Mealy Mountains, with the aim of reconnecting the younger Innu generation with the lands they have lived on for nearly 8,000 years.

I don’t want to see my children lose everything. I don’t want them to lose their Innu identity, culture and life, she told a Survival International researcher. Before I’m gone, I have to teach the children. If nobody teaches our children, what will they think when they grow up? Will they think ‘I’m not Innu, I’m a white person’?

It is important to know who you are. I am Innu. The country is my life. I’m proud that I was born in a tent. No nurse, no doctor. My father helped my mother give birth.

When I walk into the country, I feel like I’m going home, into my own place. The Innu place.

Elisabeth began her 13th – and final – walk in February 2014. Before she set out, however, she discovered that she has been denied access to ancestral Innu land around Muskrat Falls by energy company Nalcor corporation, which is constructing a hydroelectric mega-project in the area.

© Elizabeth Penashue

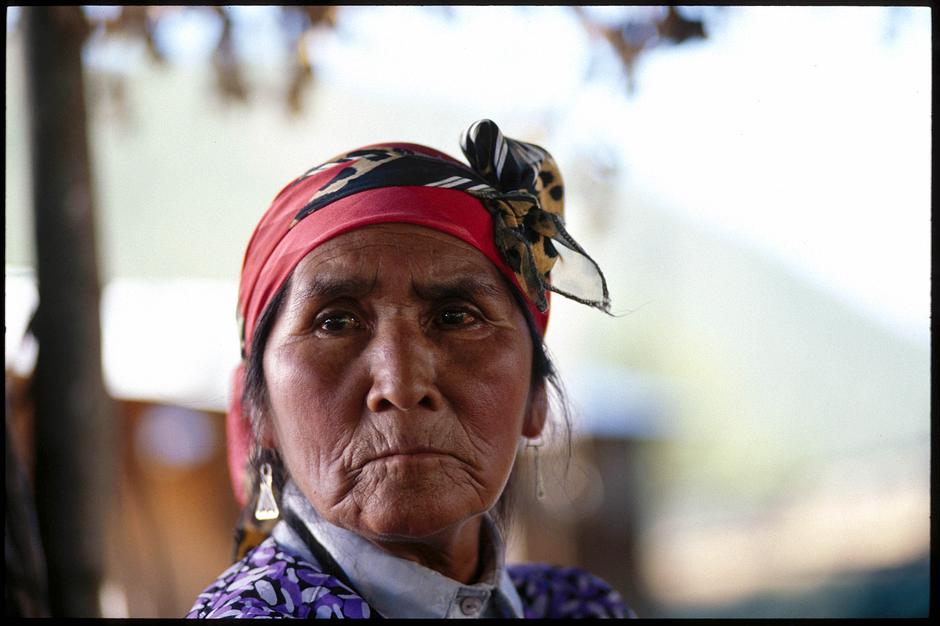

Damiana Cavanha is from the Guarani tribe, thought to have been one of the first peoples to be contacted after Europeans arrived in South America.

Once occupying a homeland of forest and plains in Brazil totaling some 350,000 square kilometers, the Guarani hunted freely for game on their homelands, and planted manioc and corn in their gardens. During the past 100 years however, almost all their forest land has been stolen from them and turned into vast, dry networks of cattle ranches, soya fields and plantations of towering sugar cane.

A decade ago, cattle ranchers intimidated Damiana and her family, evicting her from her ancestral lands. She has since lived in squalid conditions by the highway; her husband and three of her sons have been run over and killed on the road.

In September 2013, however, she led a courageous and dangerous ‘retomada’ (re-occupation) of the sugar cane plantation that has taken over her ancestral land. A ‘retomada’ had long been Damiana’s hope and solace: the goal that sustained her through the brutal years of eviction, fear, humiliation, malnutrition, bereavement, illness and depression.

We decided to fight and die for our land, she said.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia form the world’s highest coastal range; the snowy peaks that tower over cloud-forested slopes and melt-water rivers are sacred to the indigenous Arhuaco people and their neighbours, the Kogi, Arsario and Kankuama.

The Arhuaco have lived here for centuries. To them, the Sierra Nevada is the heart of the world; they call themselves the ’Elder Brothers’, and believe that they have a mystical wisdom and understanding which surpasses that of others.

Leonor Zalabata, an Arhuaco leader who has worked tirelessly in defence of the Arhuaco and the rights of Colombia’s 102 indigenous peoples, first met Survival International during the 1990s when left-wing guerrilla insurgents and units of the Colombian army set up camp on the Arhuaco’s land and subjected them to a period of brutal violence. Many Arhuaco leaders were killed.

Despite the continuing dangers, Leonor has dedicated her life to speaking out against abuses against Colombian Indians. She has worked with the UN Working Group for Indigenous Peoples and the UN Permanent Forum for Indigenous issues.

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta … is the heart of the world she says. Here is where our spirits rest and remain.

When a girl is born, in our culture we say that the mountain laughs and the birds cry.

© Survival

Since Bangladesh became independent from Pakistan in 1971, the indigenous Jumma people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the mountainous south-east region have endured some of the worst human rights violations in Asia.

Gentle, compassionate and religiously tolerant, the Jumma differ ethnically and linguistically from the Bengali majority.

Today, they are almost outnumbered by settlers and brutalized by the military.

Sexual violence against Jumma women and young girls is also alarmingly high: during 2013, at least 11 Jumma women and girls were subjected to sexual assaults, although the number may well be higher; rape often goes unreported due to its social stigma.

Little has been done to prosecute the perpetrators of these crimes, said Sophie Grig of Survival International. This leaves Jumma women and girls increasingly vulnerable, as their attackers act with impunity.

© Mark McEvoy/ Survival

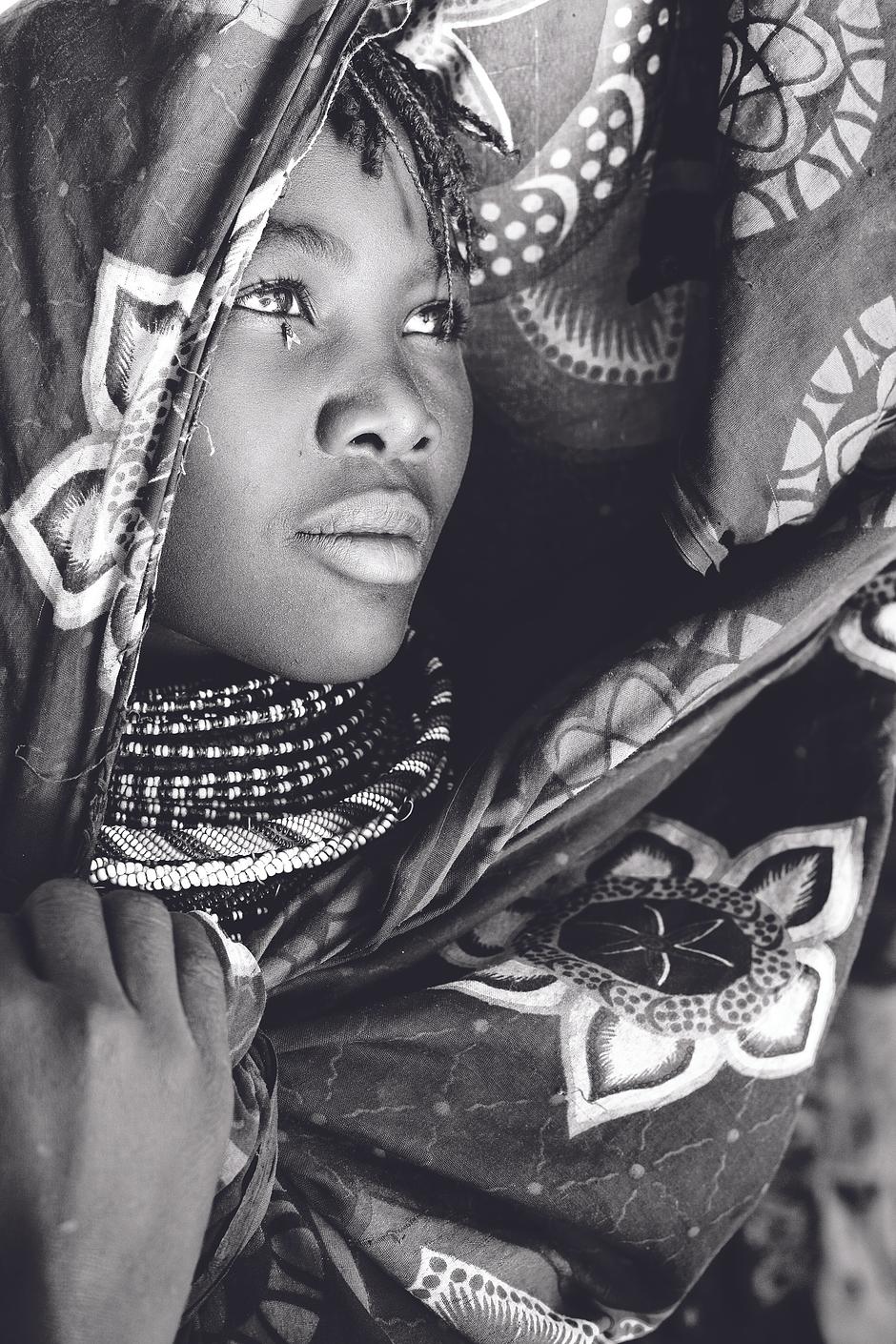

To be a Dongria Kondh woman of the Niyamgiri hills in Odisha state, India, is to be intimately connected to one’s homeland; they have lived successfully in the lush forested hills with their perennial streams and giant jackfruit trees for millennia. They call themselves Jharnia, or, protectors of streams.

For the past 10 years Dongria Kondh women have been standing shoulder to shoulder with Dongria men to protect Niyamgiri against devastating plans by British mining giant, Vedanta Resources, to construct an open-pit bauxite mine on their most sacred mountain, Niyam Dongar, the ‘mountain of law’. At one time they formed a human chain around the base of the mountain to prevent Vedanta’s bulldozers from destroying it.

In August 2013 the Dongria Kondh overwhelmingly rejected the plans by notorious British mining giant Vedanta Resources for an open-pit bauxite mine in their sacred Niyamgiri Hills – an unprecedented triumph for tribal rights. Many of the Dongria’s key figures – those who had protested loudly, travelled over 1,600 kilometers to Delhi, demanded that police release arrested leaders – have been women.

We will not give our forests to anybody, said one Dongria woman. All the women here are prepared to go to jail for this.

In January 2014, their persistence paid off: the Indian government announced that the mine would not be approved.

© Jason Taylor

The ancestors of the Jarawa tribe of the Andaman Islands are thought to have been part of the first successful human migrations out of Africa.

The nomadic hunter-gatherers only started to come out of their forest without their bows and arrows and have friendly contact with their neighbors in 1998. Now, however, the Jarawa face being wiped out unless a trunk road that cuts through their forest land is closed permanently to settlers, poachers, loggers and tourists and their lands are protected.

In early 2014, Survival International published evidence revealing the shocking extent of the sexual exploitation of young Jarawa women. A Jarawa man reported that poachers regularly enter his tribe’s protected reserve and lure young Jarawa women with alcohol or drugs, in order to sexually exploit them.

Sexually transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS are a grave threat for recently contacted tribes such as the Jarawa. The Jarawa’s neighbors, the Great Andamanese, were nearly extinguished by diseases brought in by the British colonizers in the 19th Century, which included syphilis.

© Survival

The shocking irony surrounding the 73 year old Nicolasa Quintreman’s death was inescapable.

A Pehuenche Mapuche Indian, Nicolasa had peacefully protested against the construction of the Ralco dam on the sacred Bío Bío river in Chile, which flows through their ancestral territory from the Galletué lagoon to the Pacific.

For a decade, the diminutive Nicolasa and her sister Berta refused to move from their homes, and with the support of a group of fellow Mapuche, blockaded mountain roads and bridges in order to prevent the hydro-electric power company, Endesa, from gaining access to the dam’s construction site. Many Mapuche were arrested; many more were labeled as ‘terrorists’ for their peaceful protests in defence of their homelands.

Ultimately, Nicolasa, her sister and Mapuche communities were forced to move from their homes to higher ground. They were promised financial compensation and other incentives for their displacement, many of which were allegedly not delivered.

In December 2013, Nicolasa Quintreman was tragically found floating in the Ralco reservoir, the same artificial lake she had tried to prevent Endesa from constructing.

We, who are here, we have to be here, we must defend while we can, she reportedly said.

You do not come to my house to tell me what to do. I am as I am. My land has not damaged or violated anyone. So I will never tire of fighting for it.

© Joël Philippon/Survival

It took the women and children five days to ride from the Mapuche village of Primer Corral in Chile, along the Puelo and Manso rivers, to Puerto Varas in southern Chile.

Known as Mujeres Sin Fronteras – Women without Borders – the group consisted of forty Chilean, Argentinian and indigenous Mapuche women. Theirs was a journey of protest; they were riding to draw attention to the building of dams in the Puelo-Manso watershed, which is shared by Chile and Argentina.

We are women from this valley who are worried about the destruction of our communities and of the environment, said Maria Isabel Navarrete, Mujeres sin Fronteras President.

We want to defend our tradition, our earth, and the future of our children.

© Loreto Panitao

In the depths of the Brazilian Amazon, ‘Little Butterfly’, as she is known to her tribe, swings across a river on a liana vine.

Littler Butterfly was born into the Awá tribe – the most threatened tribe on Earth. For centuries, the Awá’s way of life has been one of symbiosis with the rainforest. First contact with FUNAI, the Brazilian government’s indigenous affairs department, took place in 1973.

Today, the 450 members of the Awá tribe are surrounded on all sides by ranchers, loggers and settlers who have invaded and killed with impunity. Entire Awá families have been massacred; ancient trees have been chopped and burned. A Brazilian federal judge described the Awá’s situation as, ‘a real genocide.’

Little Butterfly lives in a village 30 minutes’ walk from the frontier, where settlers are burning the Awá’s forest day and night.

At the start of 2014, the Brazilian government finally launched a ‘major ground operation’ to evict illegal invaders from the Awá’s land, as a result of Survival’s international campaign. It was described by Stephen Corry as, a momentous and potentially life-saving occasion.

The future of Little Butterfly depends on the success of the ground operation, and on a long-term solution to stop the invaders from returning.

© Survival International

Tribal women have known brutal displacement, fear, murder and rape at the hands of invaders, for decades. They have suffered humiliation by governments that perpetuate the idea that they are somehow ‘backward’ or ‘stone age’.

They have seen their lands taken from them, their self-respect annihilated and their futures become uncertain. Even in the 21st century, the myth exists that tribal women and their communities are doomed archaic peoples that are destined to die out naturally.

But it is only the concept that is antiquated. Tribal women are not ‘backwards’ or ‘primitive,’; they have complex, evolving societies that flourish when they are left alone to pursue the self-sufficient and diverse ways of life they have developed over centuries. Despite their suffering, the resistance of many tribal women today is growing.

Survival International has been helping tribal peoples defend their lives, protect their lands and determine their own futures for over 45 years. It will continue to do so until tribal women and their families are allowed to remain on their lands, and live as they choose.

© Matilda Temperley / www.matildatemperley.com

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...

![Pocahontas was the daughter of Wahunsonacock, the chief of the Native American Powhatan Indians. The Powhatan Indians were a confederacy of about 30 tribes; their homeland was the area known to European settlers as Virginia.

Pocahontas' real name was Matoaka; Pocahontas was a nickname, meaning 'little play thing'. Aged 12, she is thought to have saved an Englishman named Captain John Smith from execution, after he was captured by a group of Powhatan men.

Pocahontas was taken prisoner by the English in 1613. During captivity she changed her name to Rebecca, converted to Christianity and married Englishman John Rolfe, with whom she had a son, Thomas Rolfe. John Rolfe and Pocahontas sailed to England in 1616, where she was presented to King James I and introduced to members of English high society - as a 'civilised savage'.

At the start of their voyage home to the U.S. in 1617, Pocahontas became seriously ill, and died in Gravesend, U.K., at the age of 22. An entry in Gravesend church parish register where she was buried reads:

_Rebecca Wroth wyffe [wife] of Thomas Wroth gentleman a Virginia Lady borne was buried in the Chauncell [chancel]_.

Her son Thomas later returned home. Many people claim to be descended from Pocahontas.](https://assets.survivalinternational.org/pictures/7566/width940-769c88f46abbf3b945c23eeda33d1547.jpg)