Tribal Heroines

On International Women’s Day, Survival International profiles the stories of inspiring tribal women around the world who are fighting for their fundamental human rights.

To be a Dongria Kondh woman of the Niyamgiri hills in Odisha state, India, is to be intimately connected to one’s homeland; they have lived successfully in the lush forested hills with their perennial streams and giant jackfruit trees for millennia. They call themselves Jharnia, or, protectors of streams.

For the past 10 years Dongria Kondh women have been standing shoulder to shoulder with Dongria men to protect Niyamgiri against devastating plans by Vedanta Resources to construct an open-pit bauxite mine on their most sacred mountain, Niyam Dongar, the ‘mountain of law’. At one time they formed a human chain around the base of the mountain to prevent Vedanta’s bulldozers from destroying it.

In August 2013 the Dongria Kondh have overwhelmingly rejected plans by notorious British mining giant Vedanta Resources for an open-pit bauxite mine in their sacred Niyamgiri Hills, in an unprecedented triumph for tribal rights. Many of the Dongria’s key figures – those who have been protesting loudly, travelling over 1,600 kms to Delhi, demanding that police release arrested leaders – have been women.

The results of the consultations will now be considered by India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests, who will have the final say on the mine – but few still believe that the mine will be given the green light. The Dongria Kondh women are as defiant as ever. We will not give our forests to anybody, said one. All of the women are prepared to go to jail for this. And even if you threaten to kill us, we will carry on living here peacefully.

I will not leave my Niyam Raja until I die.

In 2013, Survival International launched its Proud not Primitive campaign, to challenge the fact that tribal peoples in India are seen as ‘primitive’.

© Jason Taylor

When Roman Catholic missionaries arrived on the shores of the Labrador-Quebec peninsula in north-eastern Canada, many were horrified by Innu Indian women’s level of independence and power. The programme of missionary activity up until the mid 20th century heavily emphasized changing the gender roles to make them conform to the European pattern.

Until recently, women in Europe were generally seen as inferior to men, denied opportunities to succeed in society, and their role was to complement and support their husbands. Yet Innu women of the same era were far freer within and outside marriage, and often chose where and when to camp on their long journeys across the sub-arctic expanses of their homeland, Nitassinan.

This independence scandalized the Jesuit missionaries, who tried repeatedly to impose European standards by making Innu women subservient to their husbands, but it only succeeded after the Canadian government coerced the Innu to abandon their migratory way of life and live in village settlements, says Professor Colin Samson, who has worked with the Innu people for decades.

Nonetheless, Innu women in recent years have been leaders in the resistance to low-level flight training over their lands, which scares away animals used for food, and has a negative impact on physical and mental health.

They have also been prominent in opposing extractive industries on Innu lands, and have been active in efforts Innu people are making to maintain their way of life.

© Dominick Tyler

Elizabeth ‘Tshaukuesh’ Penashue is an 84 year old Innu woman from Sheshatshiu in Labrador.

For many years she has led a spring-time walk through the local Mealy Mountains, with the aim of reconnecting the younger Innu generation with the lands they have lived on for nearly 8,000 years.

I don’t want to see my children lose everything. I don’t want them to lose their Innu identity, culture and life, she told a Survival International researcher. Before I’m gone, I have to teach the children. If nobody teaches our children, what will they think when they grow up? Will they think ‘I’m not Innu, I’m a white person’?

It is important to know who you are. I am Innu. The country is my life. I’m proud that I was born in a tent. No nurse, no doctor. My father helped my mother give birth.

When I walk into the country, I feel like I’m going home, into my own place. The Innu place.

© Elizabeth Penashue

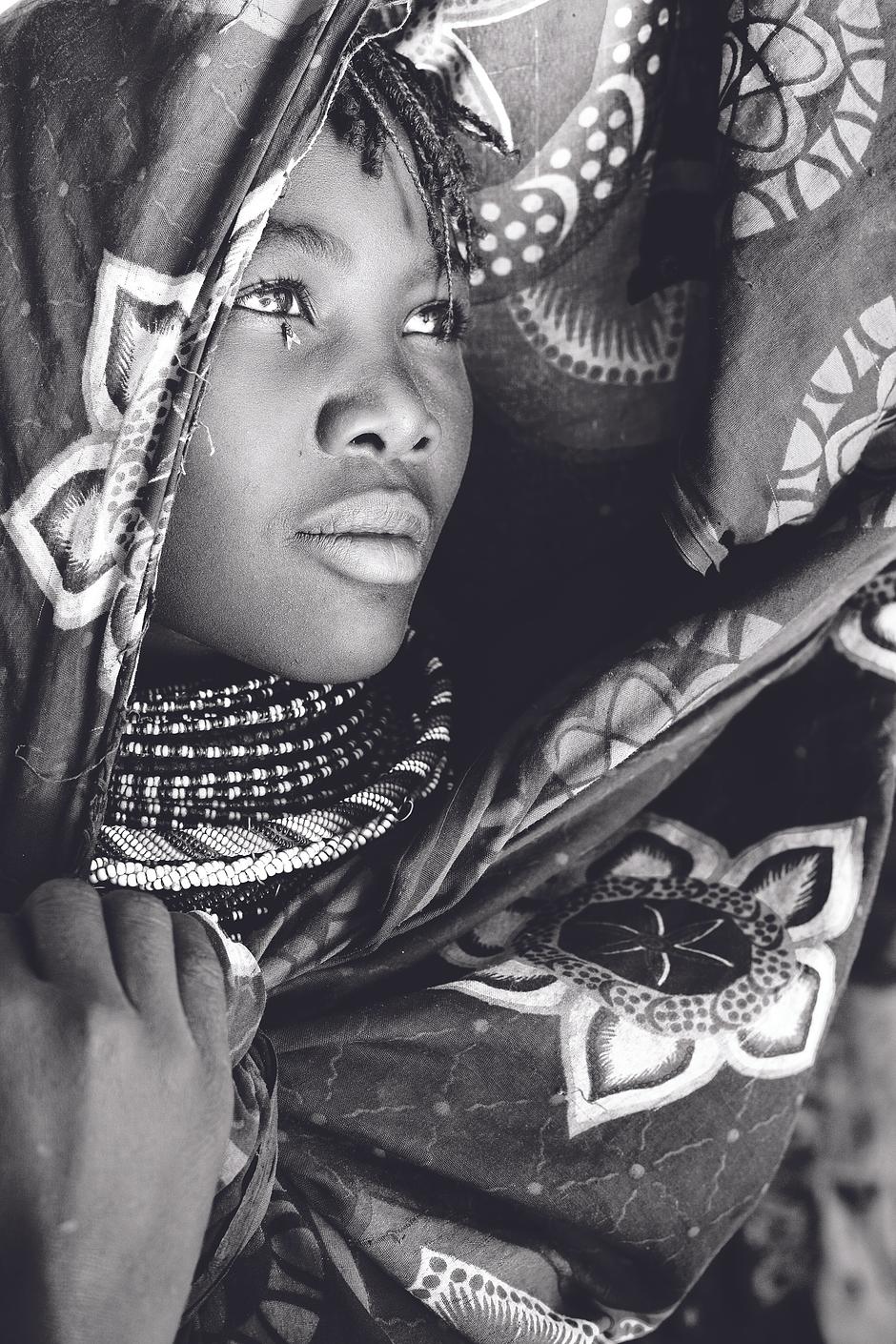

Between the soda waters of Tanzania’s Lake Eyasi and the ramparts of the Great Rift Valley live the Hadza, a small tribe of approximately 1,300 hunter-gatherers: one of the last in Africa.

The Hadza have probably lived in the Yaeda Chini area for millennia. Genetically they are one of the ‘oldest’ lineages of humankind. Over the past 50 years, however, the tribe has lost 90% of its land.

The Hadza value equality highly, recognizing no official leaders. As a result, Hadza women have a great amount of autonomy and participate equally in decision making with men.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia form the world’s highest coastal range; the snowy peaks that tower over cloud-forested slopes and melt-water rivers are sacred to the indigenous Arhuaco people.

The Arhuaco have lived here for centuries. To them, the Sierra Nevada is the heart of the world; they call themselves the ’Elder Brothers’, and believe that they have a mystical wisdom and understanding which surpasses that of others.

Leonor Zalabata, an Arhuaco leader who has worked tirelessly in defence of the Arhuaco and the rights of Colombia’s 102 indigenous peoples, first met Survival International during the 1990s when left-wing guerrilla insurgents set up camp on the Arhuaco’s land and subjected them to a period of brutal violence. Many Arhuaco leaders were killed.

Despite the continuing dangers, Leonor has dedicated her life to speaking out against abuses against Colombian Indians. She has worked with the UN Working Group for Indigenous Peoples’ and the UN Permanent Forum for Indigenous issues.

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta … is the heart of the worldshe says. Here is where our spirits rest and remain.

When a girl is born, in our culture we say that the mountain laughs and the birds cry.

© Survival

I am Angel Maria Torres’s widow, began Dilia Torres, when she greeted a Survival International researcher who had trekked through the mountains to her Arhuaco village home.

In November 1990, Dilia’s husband, Angel María Torres and two other Arhuaco leaders left their home in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region to travel to Colombia’s capital, Bogotá.

They never returned. A warm, smiling woman, Dilia recounted her tragic story calmly.

It took 10 days before we received news that my husband never reached his destination. Angel and the other men had been kidnapped, tortured and killed. When they found my husband, his fingers were missing and he had no hair left.

I have now lost all prospects of a life with my partner and family. And I think indigenous people will continue to be targeted without any justice.

This is how it is now. We have to learn to live quietly, and in constant fear. But we are Arhuaco. So they should treat us like Arhuaco.

© Survival

A Nenets woman outside her chum (tipi) in Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula. Her homeland is a remote, wind-blasted place of permafrost, serpentine rivers and dwarf shrubs; the reindeer-herding Nenets people have migrated across it for over a thousand years.

During the winter, the women endure temperatures that plummet to -50C. This is when most Nenets graze their reindeer on moss and lichen pastures in the southern forests, or taigá. In the summer months, when the midnight sun turns night into day, the women pack up camp and migrate north with their families.

Today, their ways of life are severely affected by oil drilling and climate change. Their migration routes are now affected by the infrastructure associated with resource extraction; roads are difficult for the reindeer to cross and they report that pollution threatens the quality of the pastures.

The reindeer is our home, our food, our warmth and our transportation, said a Nenets woman.

Since Bangladesh became independent from Pakistan in 1971, the indigenous Jumma people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the mountainous south-east region have endured some of the worst human rights violations in Asia.

Gentle, compassionate and religiously tolerant, the Jumma differ ethnically and linguistically from the Bengali majority.

Today, they are also one of the most persecuted tribal peoples. They are almost outnumbered by settlers and brutalized by the military. In one single act of genocide, hundreds of men, women and children were burned alive in their bamboo homes.

Sexual brutality against Jumma women and young girls is also alarmingly high: since August 2012, at least 12 Jumma women and girls have been subjected to sexual violence, although the number may well be higher; rape often goes unreported due to its social stigma.

Little has been done to prosecute the perpetrators of these crimes, said Sophie Grig of Survival International. This leaves Jumma women and girls increasingly vulnerable, as their attackers act with impunity.

© GMB Akash/Survival

Brazil’s Rondônia state is a power house of ranching and agriculture which is fuelling the country’s economic growth.

In the middle of the endless yellow fields of soya and cattle ranches, there is a tiny patch of rainforest. This is all that now remains of what was once thick, lush Amazonian rainforest.

It is also the last refuge of the Akuntsu, once a thriving Amazonian tribe. Most of their people were massacred by gunmen hired by invading ranchers.

Today, only 5 Akuntsu are still living; three of them are women. They lost their matriarch, a woman called Ururú, in October 2008.

In a few decades from now, an entire people with their own view on the world will have gone, said Fiona Watson of Survival International, who has visited the Akuntsu.

Humanity will be the poorer as yet another piece of our rich diversity disappears forever.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

The Bushmen are the original people of southern Africa. They can uniquely claim to be the ‘most indigenous’ peoples in the world, having lived on their lands longer than anyone else has lived anywhere.

In the 1980s, it was discovered that the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) lies in the middle of the richest diamond fields in the world.

Between 1997 and 2002 almost all Bushmen were taken from their homes in the CKGR and driven to eviction camps outside the reserve, where they were not only deprived of their ways of life, but humiliated by endemic racist attitudes. How can you have a stone age creature continue to live in the age of computers? asked Botswana’s former President, Festus Mogae.

Some Bushman women and their families have now returned to the reserve, but harassment and intimidation continue. In January 2013, reports emerged that some of their children had been arrested for possessing antelope meat.

Let them call us primitive. Let them call us Stone Age people. Our way of life suits us. We have seen their development, and we don’t like it, said a Bushman woman.

© Survival International

Xlarema Phuti, a Bushman woman healer, was forcibly evicted by the government from Molapo, her ancestral land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, to New Xade, a government eviction camp known as ‘the place of death’. Here, Bushmen are dependent on government hand-outs, hunting is banned and depression, alcoholism and HIV are rife.

Xlarema talked to Survival International about the healing powers of the Bushman’s traditional trance dance, and the sadness she has experienced since being evicted from her lands.

When I’m dancing in the trance dance I talk with the ancestors to help me heal the sick person.

I was still a young person when I became a healer. I dreamed and the dancing and healing started. When I started to dance I could feel a person by their blood and smell.

I was able to heal well at Molapo because there were a lot of ancestors there who I can talk with. The ancestors speak through my blood. But there are not as many ancestors in New Xade, so my powers of healing are weaker. And some diseases are very difficult to cure, such as HIV/Aids.

We never knew this disease before.

© Dominick Tyler

Boa Senior from the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean was the last remaining speaker of the Bo language. The ancestors of Boa Senior and other tribes of the Andaman Islands, such as the Jarawa, are thought to have been part of the first successful human migrations out of Africa

Boa Senior died in 2010. Nearly 55,000 years of thoughts and ideas – the collective history of an entire people – died with her.

They don’t understand me. What can I do? Boa Senior asked before she died. If they don’t speak to me now, what will they do once I’ve passed away? Don’t forget our language, grab hold of it.

The Jarawa face a similar fate to Boa Senior unless a trunk road that cuts through their forest land is closed permanently to settlers, poachers, loggers and tourists. Before the Indian Supreme Court passed an interim order in January 2013 banning tourists from using the Andaman Trunk Road, hundreds of tourists traveled along the road every day in the hope of seeing the isolated Jarawa tribe.

Since 1993, Survival has been campaigning to ensure that the road is closed and the policy of minimum intervention adhered to. In a major blow to the campaign, however, the Supreme Court reversed the order in March 2013, opening the door for the exploitative ‘human safaris’ to start again.

© Alok Das

Soni Sori is an adivasi (tribal) school teacher and mother of three young children from Chhattisgarh state in India.

Soni has been an outspoken critic of the Indian government, Maoists and of steel companies such as Essar Group. She was raped and tortured while in police custody, having been accused of being a courier between Maoists and Essar Group.

Soni has now been imprisoned for 17 months, with little hope of bail – accused of a crime for which there is little evidence. Giving me electric shocks, stripping me naked, shoving stones inside me – is this going to solve the Naxal (Maoist) problem? wrote Soni in a letter to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Dr. Jo Woodman of Survival International, said, Soni Sori has suffered horrific abuse at the hands of the police and remains in their custody. But what is this really about? The state of Chhattisgarh’s desperation to silence those who speak out, while atrocities continue in the hidden war in India’s heartlands. Meanwhile, the suffering of the Adivasis of central India continues, and justice seems a distant dream.

I want to go back and help my people, said Soni Sori. I want to use my education to empower them. If we don’t learn to speak for ourselves, tribal people will be wiped out.

Many women in industrial societies still campaign for equality with men.

For women of the Awá hunter-gatherer tribe in the Brazilian Amazon, however – the most threatened tribe on Earth – equal status with Awá men is normal. Some Awá women even take several husbands, a practice known as polyandry.

The Awá are one of only two nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes left in Brazil. For centuries their way of life has been one of peaceful symbiosis with the rainforest; they are so familiar with their lands that Awá women even care for orphaned baby monkeys by suckling them.

Over the course of four decades, however, the Awá women have witnessed the destruction of their homeland and the murder of their people at the hands of ‘karaí’, or ‘non-Indians’.

© Domenico Pugliese/Survival

Little Butterfly, an Awá girl, lives in a village 30 minutes’ walk from the frontier, where settlers are burning the Awá’s forest night and day.

The future of Little Butterfly is, at best, precarious, unless her lands are protected and her rights respected.

Even in the 21st century, the myth exists that tribal women and their communities are doomed archaic peoples that are destined to die out naturally. It is the concept that is antiquated – not them. Tribal peoples are not ‘backwards’ or ‘primitive,’ they have complex, evolving societies that flourish when they are allowed to remain on their lands and live as they choose.

Yet all too often industrialized societies subject tribal peoples to genocidal violence, slavery and racism so they can steal their lands, resources and labour in the name of ‘progress’ and ‘civilization’.

On International Women’s Day please support Survival International, and help us protect tribal women’s lives, lands and human rights.

© Survival International

Don’t hold us back. We have our own talk.

Bushman woman, Botswana.

© Katherine B. Topolniski/Survival

Tribal women have known brutal displacement, fear, murder and rape at the hands of invaders, for decades. They have suffered humiliation by governments that perpetuate the idea that they are somehow ‘backward’ or ‘stone age’.

They have seen their lands taken from them, their self-respect annihilated and their futures become uncertain.

Yet despite their suffering, the resistance of many tribal women is growing. Survival International’s photographic gallery to celebrate International Women’s Day, backed by Survival Ambassadors actress Gillian Anderson and jeweller Pippa Small, reflects not only the many tragedies that tribal women have endured, but also profiles some of the courageous and inspiring women who are fighting for their lands to be returned to them and for their fundamental human rights.

© Matilda Temperley / www.matildatemperley.com

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...